Genetic Mutation Accelerates CTE Pathology

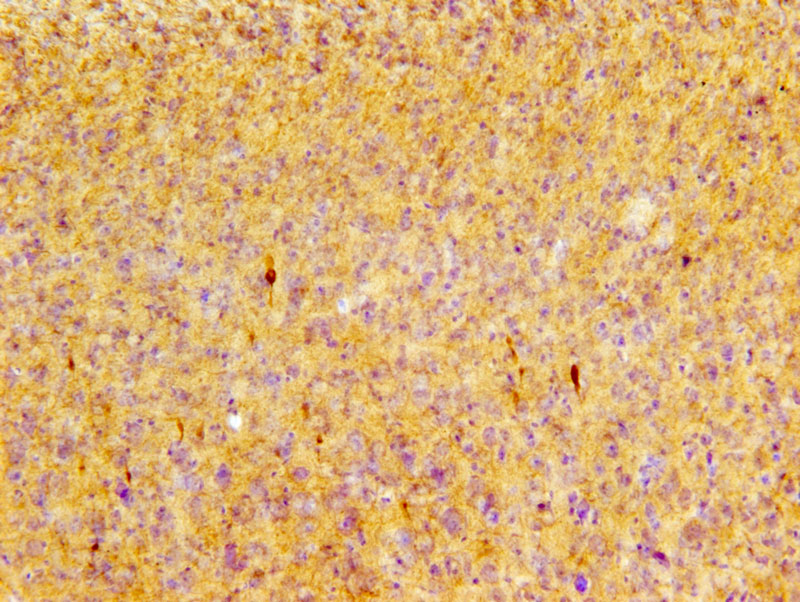

Phosphorylated tau pS422 immunoreactive profiles (dark brown) in the cortex of P301S mice after repetitive mild TBI. Image courtesy of Dr. Leyan Xu, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University.

Over the course of a football game or a boxing match, athletes may experience a series of mild concussions. Some of these athletes develop a condition known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the build-up of abnormal tau protein that eventually leads to dementia. But not every athlete develops CTE after repetitive mild traumatic brain injury, and scientists think genetic factors are involved.

In a recent study, researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine found that the density of abnormal tau protein increased exponentially in mice that had a genetic mutation thought to cause neurodegenerative diseases. Their findings contrast with previous studies of mice without genetic mutation, where abnormal tau protein build-up did not occur. This evidence leads the scientists to infer that genetic factors play a role in the onset of CTE.

According to the paper, published in Experimental Neurology, scientists have identified 40 different types of mutations in the gene that makes the brain prone to tau aggregation. “Transgenic mice harboring these mutations can be used to ask whether repetitive mTBI can accelerate onset and course of tauopathy or worsen the outcomes of transgenic disease,” the authors say in their paper.

In this study, Dr. Leyan Xu and his team examined the P301S strain of transgenic mice which harbor a tau gene mutation. After exposing the animals to a series of impact acceleration (IA) injuries involving a weight drop technique, the researchers examined both the neocortex and the retina. The visual tract is a pathway strongly associated with TBI in this mouse model, which is why the researchers investigated the retina in addition to the neocortex.

Using the optical fractionator probe in Stereo Investigator, they analyzed neocortical neurons immunohistochemically labeled with a marker for hyperphosphorylated tau protein – in other words, tau gone awry. They did not witness significant differences in tau build-up between the neocortices of the experimental mice and control mice, however they did see differences between these groups when they examined their retinas. Their findings revealed a 20 fold increase in retinal ganglion cells with hyperphosphorylated tau after one mTBI hit in transgenic mice, compared to controls, a 50 fold increase after four hits, and a 60 fold increase after 12 hits. Both experimental and control mice displayed similar patterns of traumatic axonal injury.

“Our current findings demonstrate that repetitive mTBI accelerates tauopathy in mice predisposed to tau accumulation. A single mTBI event also appears to have an effect in the progression of tauopathy, but repetitive injury has an even greater effect,” (Xu, et al)

Xu, L., Ryu, J., Nguyen, J.V., Arena, J., Rha, E., Vranis, P., Hitt, D., Marsh-Armstrong, N., Koliatsos, V.E., (2015) Evidence for accelerated tauopathy in the retina of transgenic P301S tau mice exposed to repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. Experimental Neurology. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.08.014